Creativity and innovation are necessary for development and survival in a modern world in which problems and challenges such as war, disease, and global warming are complex issues with unpredictable consequences. In many aspects of life, from economics to politics or from education to the sciences, governments need to set up clear and explicit strategies that consider creativity as a cornerstone. If they do not place creativity, a prerequisite for innovation, as their highest priority, policymakers cannot expect workers or employees to behave creatively and accept ingenuous changes. Governments that believe creativity is a valuable human resource will invest and support originality in their plans and initiatives.

This article offers a scientific and workable definition for the concept of “creative government” – a term that is uncommon and rarely discussed in scientific literature. To realize this notion, it is important to: discuss the differences between individual and organizational creativity; describe the characteristics of a government that supports creativity; stress the significance of supporting creativity in k-12 education; specify environmental factors that encourage creativity in the government; and describe ways in which governments can support creativity research.

Before aiming to define the creative government, it is important to define the term “government” itself. Let me begin with a simple definition: according to the Oxford Dictionary, “government” refers to a group of people who are responsible for controlling a country or state. The expression “group of people” requires us to elaborate on the differences between individual and organizational creativity.

Individual vs. Organizational Creativity

Over the past six decades, creativity research and researchers have mainly focused on the individual, rather than the broader organizational level. Consequently, the focus has been on studying: (a) characteristics distinguishing creative individuals – such as risk-taking, openness to experience, and independence; (b) creative processes in which original and effective ideas are being produced (e.g., brainstorming, problem finding, and creative problem-solving); (c) mechanisms in which creative ideas are being transformed into tangible products; and (d) environmental factors that foster and encourage creativity and creative behavior. However, the past two decades have witnessed an increase in studying creativity and innovation in organizations – as evidenced in books, peer-reviewed articles, and policymakers’ speeches, national plans, and strategies. For a government that seeks creativity and innovation, it is equally important to consider both individual andorganizational creativity. Nevertheless, the mechanism of individual creativity is somewhat different from that of organizational creativity.

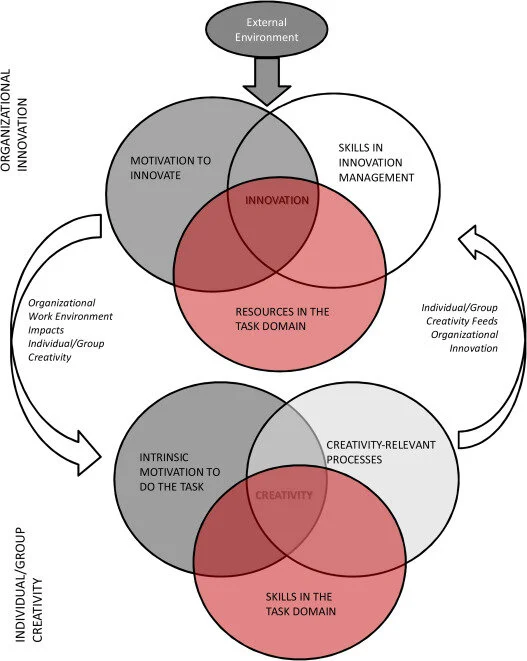

Teresa Amabile, a professor at Harvard Business School, developed a dynamic model of creativity and innovation in organizations in which both individual and organizational creativity dynamically interact with one another. While creativity in organizations requires skills in innovation management, the motivation to innovate, and resources in the task domain, individual creativity requires creativity-relevant processes, intrinsic motivation, and skills in the task domain.

Note that the term “innovation” was used when describing elements of organizational creativity, whereas the term “creativity” was used to denote individual creativity. Although these two concepts overlap, they are different in at least three ways. I will briefly discuss this difference, given the limited space available to me. First, I begin with one commonality between innovation and creativity: they both refer to ideas and products that are both novel and useful. However, creativity and innovation differ in their novelty-usefulness ratio. Whereas innovation requires new ideas with a main emphasis on utility, creativity requires a greater degree of originality or novelty. The second difference is that the term “creativity” is ideal for use in the k-12 educational context, where the focus should be on encouraging new and uncommon ideas rather than developing actual products – especially given that students in earlier stages do not usually have enough resources to transform their creative ideas into tenable products. Third, creativity is a prerequisite for innovation; without creativity, there is no innovation. The rest of this article aims to answer the following two questions: (a) When does creativity begin in the context of government work? and (b) What are the characteristics of the creative government? Once these two questions are answered, it will be easy to define the term “creative government.”

When does creativity begin?

Some studies suggest that creativity begins when a government provides a psychologically safe environment in which employees are encouraged to express their ideas freely, are able to take creative risks, and wherein they can receive rewards and incentives (extrinsic motivation) based on their performance. Others believe that creativity exists when policymakers (those in top-level management) value originality and creative thinking. In fact, both groups are right – as evident by empirical studies and observations; however, some researchers (including the writer of this article) believe that governments can invest in creativity at an earlier stage by nurturing and supporting imaginative thinking from childhood. To support this argument, I briefly shed light on three pieces of empirical evidence. First, based on several studies that were conducted on thousands of k-12 students, creative thinking starts to decrease when students reach the fourth grade, a phenomenon that is known in the scientific literature as the “fourth-grade slump.” This decrease in creative thinking skills is due to the nature of the school curriculum, which only focuses on logic and logical thinking, and thus, resists imaginative and uncommon ideas and solutions. Second, results from longitudinal studies (i.e., studying the same sample of students over an extended period of time) demonstrated that creativity in childhood, as measured by divergent thinking tests, can predict future achievements better than achievement and IQ tests. Thus, identifying and nurturing creative talent at early stages is, in fact, a significant investment. The third piece of evidence is from a study that was conducted on a sample of GCC women, who were asked about their personal obstacles to creativity. Here is a sample of their responses: I would be more creative if: (a) I was prepared to take more risks, (b) I was more stimulated by my teachers, (c) I had more opportunities to be wrong without being considered stupid or an idiot, and (d) I had a greater acceptance of the fantasy in the way that I live. There is nothing better than concluding this section with a quote from E. Paul Torrance, who is often called the father of creativity:

“It is my firm belief that every educator, from kindergarten through to graduate school, should always be on the alert to notice new ideas proposed by children and young people, and to encourage such individuals to continue the development of their creative talents. Every educator should consider this as important or more important than teaching information.”

The Characteristics of Creative Governments

Unsurprisingly, very few studies have explicitly studied the characteristics that apply to creative governments. As indicated earlier, this is mostly because the term “creative government” is still uncommon/not widely used. However, studies from the field of organizational creativity have suggested some characteristics of creative organizations. These features include the following:

· Finding different ways of motivating workers

· Valuing creativity and creative thinking

· Offering a degree of freedom and autonomy for employees

· Providing sufficient materials, both physical and intellectual

· Rewarding and recognizing creative ideas and projects

· Offering challenging work for employees

· Considering a physical environment that encourages creativity

· Treating employees fairly with clear criteria

· Providing advanced training for employees

· Encouraging diverse ideas and communication between employees in different departments, and

· Searching for, and attracting, members of the creative class.

The final point is of great importance: the concept of the creative class was coined by the well-known economist Richard Florida, and refers to a group of people believed to bring economic growth to countries. No matter how good your education is, or how good your scholarship system may be, a society will always need to attract creative people from around the globe. I will elaborate on how to attract the creative class in another article. For now, it is enough to say that one very important characteristic of creative governments is their ability to attract creative talent from different parts of the world.

Defining “The Creative Government”

Creativity is an invaluable human resource that can enhance quality of life. The role of the government in nurturing and supporting creativity should begin with k-12 education. Another means by which the government can invest in creativity is to support creativity research, make connections between theory and practice, create national plans and initiatives that support creativity at different levels of government, and set up policies that support creativity. This article concludes with a suggested definition of a creative government:

The creative government consists of an administration that values creativity and, thus, (a) invests in creative potential starting from k-12 education; (b) supports individuals transforming their creative ideas into tangible products (i.e., inventions) that are both novel and useful; (c) supplies funds for creativity research and practice; (d) attracts talented individuals from other parts of the world by offering an ideal environment for investments; and (e) sets up clear and explicit strategies that consider creativity as a corner stone.

References

- Abdulla Alabbasi A. M. (2020). Government. In M. A. Runco & S. R. Pritzker (Eds.), Encyclopedia of creativity (3rd ed., pp. 555-561). San Diego, CA: Elsevier. https:/ doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12- 809324-5.23657-2

- Amabile, Teresa M., and Michael G. Pratt. "The Dynamic Componential Model of Creativity and Innovation in Organizations: Making Progress, Making Meaning." Research in Organizational Behavior 36 (2016): 157–183.

- Torrance, E. P. (1995). Creativity research. Why fly? Westport, CT, US: Ablex Publishing.